These ARE the drugs you're looking for...

13 Jedi mind tricks to boost adherence

Despite our ever-growing wealth of knowledge about disease, and development of new ways to fight it; these efforts are meaningless if they cannot be applied in real life, to real patients and their problems..

In medical training the focus is mostly upon mastering the core elements of practice: history, examination, investigation, diagnosis, and deciding the best evidence-based treatment options for the patient in front of us. While indisputably valuable, this completely neglects a phenomenon that truly rate-limits healthcare professionals from applying any of these abilities. Something which prevents the achievement of treatment potential in every speciality, globally. Something we should all know more about.

I’m speaking about non-adherence.

Even if we manage to recognise, investigate, diagnose, and prescribe the correct treatment for a problem, this is all in vain if the treatment is not followed; if our advice falls on (metaphorically) deaf ears.. If a patient won’t take their antihypertensives and suffers a stroke.. If a patient doesn’t give up smoking before it causes lung cancer.. If neglect of physiotherapy results in functional deterioration and permanent disability..

Medical research has consistently shown scarfiying levels of non-adherence, where about half of prescribed medications are taken incorrectly (or not at all) in the developed world. It’s even worse in developing countries, with levels as low as 26% noted. This results in vast waste of healthcare investment (an estimated 33% less cost effectiveness for treatment), losses in health and quality of life, promotion of social inequality, perpetuation of chronic disease and disability, and has impact upon national economy through lost potential working days. Hashtag drama bomb.

The authors of a thorough systematic review of randomised controlled trials studying non-adherence, concluded that:

“Increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medicaltreatments” (source)

I find the quote quite empowering. Having a significant positive impact on your patients and populations doesn’t require a triple PhD, nobel prize, and the discovery of a game-changing treatment. You can potentially make a far bigger impact by just doing the simple things well. By getting the maximum effect from treatments offered, by facilitating excellent adherence.

To write this article I explored medical and psychology research on non adherence, and influencing behavioural change. This resulted in the discovery of 13 ‘Jedi mind tricks’ which doctors have been using to combat these problems, and I share below..

Adherence vs compliance

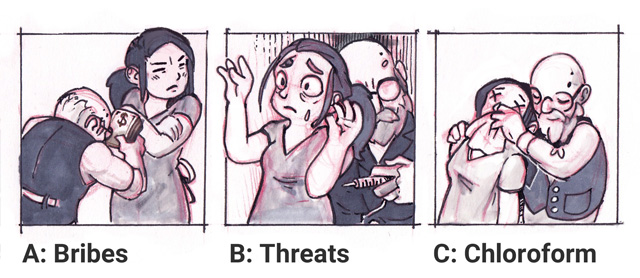

First, a quiz: how can doctors best get patients to follow their advice?

A and B are clearly false. C however, is also. If you don’t want to lose your medical license.. To understand the issue of non-adherence we need to look at it from the right perspective. Patients are not passive recipients who merely ‘comply’ with a doctor’s imposed will, as is the case with these options. It is natural to want to resist forced influence of any kind. This can be avoided by involving patients as active collaborators when building treatment plans, and has the added benefits of encouraging patient autonomy, adherence, and responsibility for their health.

Why don’t patients follow doctors’ advice?

I’m not your patient; why would I know? (He writes, ignoring the fact that he wrote this article about it.) Patients are far more complex than a textbook formula; knowing how to work with them is more of an art than a fixed set of rules, as problems are usually multifactorial. Solutions should be tailored to the individual patient. Knowing their ‘reasons why’ allows for targeted solutions, and wastes far less of everyones time. So, without further ado, here’s what I discovered:

13 Jedi mind tricks to boost adherence:

#1 Avoid communication barriers

Trainees (including a naive me) may reflexively roll their eyes at the title, but it’s deceptively pertinent. The above animation illustrates a real life scenario I saw in a GP practice where a deaf patient (who relied on lip reading), missed everything the doctor said each time they turned to use their PC. In a med school geriatrics placement, I faux pas’d my way through a neurological examination of a blind lady (to her great amusement), by repeatedly asking her to “do this” (demonstrating limb positions for her to copy that she obviously couldn’t see), while running on autopilot..

Problems are easily avoided if you’re aware of them, particularly the more subtle. Some tips:

Ensure patients who need glasses and hearing aids have these on so patients have a chance to see and hear what you’re talking about.

Get down to eye level, and face the patient in a well lit area; this makes lip reading, and non-verbal communication (eg facial expression and gestures) easier to interpret. It can also empower patients by avoiding the dominating position of power that ‘standing over them’ creates.

Ensure leaflets are clear and simple, in a patients preferred language. Be aware of literacy levels too; most people haven’t spent years practicing this alien medical language we now speak.

Make use of formal interpreter services (in person or by phone) when needed. Interpretation through family and friends can result in information being avoided (eg sexual issues and abuse), lost, or manipulated.

Check the information has been understood and retained, by getting patients to explain their understanding of what you have said. A yes/no confirmation is not good enough. This helps you assess capacity, and see if you really conveyed what you intended.

#2 Use the Pygmalion effect

This describes the phenomena of inciting the behaviour expected in a person, as a result of how this expectation makes you act towards them. We can look to ‘heartsink’ patients to illustrate this: if you think a patient will ignore your advice; this attitude filters down into your body posture, tone of voice, dialogue etc, and can actually be the cause of this result! The pygmalion effect can act in a positive way too, so influence your patients with optimistic belief in their receptiveness, and don’t get too jaded!

#3 Get on the same page

Poor understanding of why treatment is needed and adverse effects patients might expect, are important factors in non-adherence. This is particularly the case for ‘silent’ asymptomatic disease such as hypertension, or high cholesterol. We as doctors can see these as a heart attack or stroke waiting to happen thanks to our training, but often forget that they can be abstract concepts to patients who don’t see or feel their effects in day to day life. For example: relating a diabetic bus drivers low blood glucose readings to potentially losing their driving license (due to risk of passing out at the wheel), can be a more meaningful incentive to achieve blood sugar control, than abstract target number ranges.

Listen to patients carefully, and direct dialogue to elicit their values, goals, and interests. Linking your advice to a patient’s goals or values (eg their job, wanting to provide for their family) allows you to springboard from their intrinsic motivation, rather than having to build this from scratch.

#4 Simplify and support regimens

Adherence is inversely proportional to regimen complexity. The more drugs, and the more inconvenient they are to take: the lower the adherence, and thus the potential benefit of the medicine is reduced, or lost entirely..

Doctors can improve adherence by simplifying treatment, e.g. using dosette boxes to make complex regimens easy to follow for an elderly patient living alone, or e.g. prescribing monthly contraceptive depot injections rather than daily tablets for cover for someone with a chaotic lifestyle who consistently misses pills.

Setting the regimen up in a phone calendar or alarms can help remind people what to take and when. Patients can help by letting their doc know when the current plan isn’t working. There’s often many different strategies and treatments that can be tried to find the best fit for them.

#5 Boost mood, motivation, & adherence

There is a strong correlation between mood, motivation, and adherence. A meta-analysis of research investigating this found that people with depression were 76% more likely to be non-adherent to prescribed drugs than patients without depression. Treatment can directly improve motivation to engage with healthcare, and indirectly aid good adherence habits by building associations between improved mood, and resolving disease symptoms.

#6 Harness expectation & the placebo effect

Do not underestimate the power of belief.. An interesting study showed that pain had a 35% response to placebo analgesia, and a 36% response to medium dose morphine (ref). Think about that: the power of the mind with a placebo, was equivalent to medium strength morphine. The research went on to show that double the analgesic effect was achieved when expecting pain relief from the ‘treatment’ (whether it was placebo or morphine), while zero analgesic effect was experienced if the participants expected pain. That is straight up hashtag cray cray!

How can this be? The experience of pain is not a simple circuit; much can interfere with the pain messages travelling in our nerves en route to the brain. We don’t always experience pain proportional to tissue damage, as those of us who have had paper cuts can testify. We also hear tales of people who accomplish incredible feats of survival, who report they didn’t feel any pain until after the danger had subsided. Pain can be modulated by our autonomic nervous system, emotional state, endorphins, competition for attention, and temporal variation in disease / symptom activity.

“Practitioners should seek to ethically maximize the benefits of positive expectation when treating pain…putting a positive spin on the potential of a pain intervention is therapeutic” (ref)

Or my less eloquent: sell the shit out of your treatments and colleagues, because it does make a difference.

#7 Support (good) habit formation

The ‘habit’ of following long term treatment (eg drugs) as prescribed, needs to be developed. If you have ever tried a new diet or exercise regimen, you can appreciate the difficulty in maintaining this consistently over time. With drugs, this can made more challenging if you experience side effects, or the benefits are invisible (eg stroke risk reduction with Statins). The first 6 months of starting a new drug are the most important in establishing a habit of good adherence, thus also for supporting a patient to achieve this.

Habits are behaviours unconsciously triggered by environmental cues, that through repetition become associated with those cues. They may be positive (eg going for a morning run) or negative (eg smoking every coffee break), and their development can be influenced by biological factors (eg endorphin release and nicotine ‘buzz’ with respect to the previous examples).

A young pregnant woman and her partner that I encountered in medical school were both addicted to heroin, but determined to bring their future child up in a better environment than they had been raised. They were able to eliminate heroin use, and achieve stability with a methadone program during the pregnancy. Subsequently, both were supported to come off methadone entirely over the next 18 months.

Methadone prevented the intense side effects of withdrawal, stopping association of this physical turmoil and ‘life without Heroin’ as they got clean. Simultaneously, the positive habit of not injecting heroin was reinforced by health, social, and financial improvements in life without it. The couple also credited their achievement to moving away from the people and places associated with their harmful habit, highlighting a partially context-sensitive nature, and the potential of avoiding triggering situations while in pursuit of a new healthy habit.

#8 Use motivational interviewing

This is a style of counselling to assess readiness, prime for, and facilitate behavioural change. The actions taken depend on where in the ‘cycle of change’ (below) a patient is. The stages:

Pre contemplation: patient believes they have ‘no problem’. Try to raise awareness, but make them welcome and comfortable to discuss the topic in future

Contemplation: patient is considering action. Resolve ambivalence, induce cognitive dissonance (detail below)

Action: active attempt to change. Identify & implement strategies

Maintenance: change achieved. Support achieved goals

Relapse: accept as part of the process, deal with it constructively & determine next steps

Actually conducting a motivational interview involves:

Open ended questions establish patients’ understanding, and identify motivations & obstacles to tailor discussion with. Ambivalence and resistance to change are tackled by working with a patients personal motivations and values, rather than a practitioners rationale. Arguments for change are made indirectly by drawing them from the patient, bypassing the natural resistance often elicited by external orders to change. Remember our diabetic bus driver from earlier? While we may care about the target blood sugar range, the risk to his license and career may be a more powerful incentive..

Affirmation is used to recognise patient strengths, focus on successes, and re-frame negative views constructively, to help plan and support an attempt to change. For example: don’t focus on the fact that they failed to abstain from alcohol 7 times, but instead, that they managed 9 months of abstinence once, proving they can do it, and pointing towards previous effective strategies that worked for them.

Reflective listening confirms/corrects your understanding, and gives opportunities to direct patient thinking by summarising with focus on the positive and useful attitudes for change. Reflection on patient-elicited statements that do not align may induce a cognitive dissonance (incongruence between attitudes/beliefs and behaviours). This tends to initiate a change in thoughts or behaviours to reduce this unpleasant feeling, one result of which can be therapeutic change.

An interesting example of creating the mental discomfort of cognitive dissonance, and reflection after, is in these viral videos. Here, a child asks adult smokers for a cigarette. Most decline, and condemn smoking as a bad habit. The child then asks ‘why are you smoking then?’ prompting a profound moment of reflection in many.

We often look to patients who abuse substances like tobacco, alcohol, and heroin as examples of ‘heartsink‘ patients, whom we often find in a ‘pre contemplative state’. Even if you cannot change a persons view immediately with your contact; the evidence we have suggests that brief interventions do work, and are worth your time broaching the topic. Your attitude and approach plays an important role in a patients reflection after, and their willingness to engage with the next healthcare professional.

#9 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) aims to change behaviour by focussing on solutions (cognitive), changing unhelpful habits, and reinforcing positive ones (behavioural aspect). CBT studies have demonstrated significant outcomes of long term improvement in traditionally hard-to-treat conditions with pathologically rigid thinking patterns, such as anorexia nervosa, obsessive compulsive disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and functional disorders.

#10 Nudge ’em

Traditional public health policy is often based on an assumption that people make poor health choices in a conscious, reflective way. Many interventions therefore aim to inform people of the risks or benefits of certain life choices, hoping that this will encourage logical healthy decisions.

However, our choices are not made in a vacuum. Our actions are heavily influenced by our environment and emotions, often involving little-to-no cognitive thought. For example, despite trying to diet; when hungry our motivation can crumble and many will shop less healthily.

Advertising specialists understand this well, and modify shop environments to influence sales in a very deliberate way. Examples of these include:

Commonly bought products eg fresh bread or milk are strategically positioned to encourage movement through many aisles, and thus create more opportunities for sales.

Carefully chosen, more expensive products are placed at average eye level to promote this as the ‘default choice’ when surrounded by similar options

Brightly stickered “deals” are used to grab attention and divert sales to new or poorly selling products, to build new buying habits and sell produce about to go off, respectively.

Packaging design and color is often used often to falsely suggest healthiness or quality

Brightly colored treats surround checkouts for children to notice and add to parents shopping while they wait in queues

Think you are immune to these forces? Have you ever gone out just to get milk, and returned home dragging 3 bags of groceries, fresh cookies, new clothes, a book, and (if you’re like me) having also forgotten the milk..

Nudging describes policy that encourages, but doesn’t force a healthier choice through outright regulation. For example: ‘making salad the default side order rather than chips’ vs ‘banning unhealthy food options‘. In Copenhagen, there is a +180% tax for purchasing cars, which encourages a physically healthier, and globally greener, culture of pedestrianism.

It is important that we all try to appreciate the factors influencing us if we are to stand a chance of resisting them. Much could be gained by harnessing the power of nudging in deliberate environments that encourage, and make healthy decisions easier.

#11 Leverage support, delegate aggressively

Has the patient got family or friends who can attend appointments with them, or help them take medication correctly? Would they benefit from additional support such as a carer, or sheltered housing?

Doctors should make full use of allied health professionals where possible, leveraging their specialist skills. This facilitates holistic care, and makes for more efficient use of everyones time. Pharmacists can often explain medication and adverse effects better than a doctor who just googled or BNF’d it. Specialist nurses often run clinics supporting management of diseases such as asthma or diabetes.

Become familiar with local self referral services (eg physiotherapy, counselling, addictions support), and online resources you approve of (eg Macmillan for cancer information, or online mental health resources). From my time rotating in Liaison Psychiatry I saw huge patient benefit by having a host of support options up your sleeve besides drugs. These allow flexible tailoring of treatment to individuals, and can provide much needed relief while patients are stuck waiting many months for secondary and tertiary service appointments.

#12 “Test close”

Check with your patient if a suggested plan of action is acceptable, and work with their response. This helps preserve the doctor-patient relationship by avoiding resistance to dictated orders, allowing collaboration to find the best acceptable solution. Simply: “What would you like to do?” can be effective; their answer confirming commitment or inviting negotiation.

Note: do not ask a yes/no question! Those answers can be highly influenced by social convention, or made without considered thought – in which case the chances of being happy with the decision and adhering will be much lower!

#13 Monitor & review adherence

Lastly (thank glob), don’t forget to evaluate and adapt to adherence. Many adverse incidents in hospital are the result of providing medication as prescribed, which is not necessarily taken at home, or taken correctly, and so their body is not able to handle these drugs or doses as expected. Aim to perform a medicines reconciliation at each new healthcare interaction to avoid harmful errors.

Gather all the data you can, ask the patient what they take, how they take it, and how much they have left. Check if repeat prescriptions are being fulfilled. Sometimes measuring for blood/urine/saliva presence or concentrations of drugs is required. Follow up patients soon after prescribing new medication to correct non-adherence at an early stage before it becomes habitual.

Conclusion

Delivering excellent healthcare requires the ability to influence positive behavioural change

Frame your advice within a context that is meaningful to the patient

Ensuring good adherence may have a far greater impact on the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments

Creating meaningful change is a collaborative process which all healthcare professionals can support, before and beyond the point of prescription

You made it to the end! Like the article? Share with someone who might appreciate it, and subscribe to catch the next one when it drops!