The 'art' of surgical consent

This is a Green Open Access version of the accepted Manuscript of “The art of consent: Visual materials help adult patients make informed choices about surgical care.“. This paper was published by Taylor & Francis in the Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine on 20/11/19, available online: bit.ly/consent-abx

The art of consent: Visual materials help adult patients make informed choices about surgical care.

Dr Ciléin Kearns, Dr Nethmi Kearns, Miss Anna M. Paisley

Abstract

Background: Supporting patients in making informed healthcare decisions is a cornerstone of ethical medical practice. Surgeons frequently draw for and show images to patients when consenting them for operations but the value of this practice in informed decision-making is unclear.

Methods: An audit was conducted in a General Surgery Department. 244 patients completed questionnaires on the value of visual materials when giving consent for surgery. The complexity of the operations were classified into “simple”, “moderate” or “complex”.

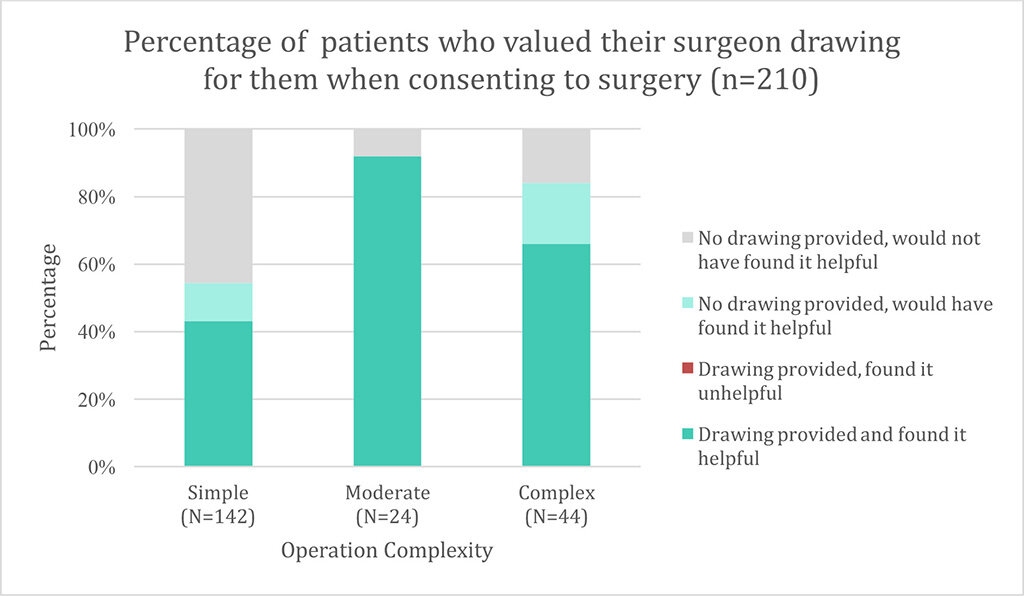

Results: 100% of patients felt they had given informed consent to surgery. 62% of patients received at least one form of visual material during the consenting process. All patients who received a drawing, and 99% of those provided with other images, valued these resources. Visual materials were considered more useful to patients when giving consent for moderate or complex operations than simple ones. Approximately one third of patients who did not receive visual materials would have appreciated these when making an informed decision.

Conclusion: This research highlights the value of surgeons drawing for, and providing other visual resources to, their patients as part of the consent process. There is a role for further research and training materials in drawing skills for surgeons.

Introduction

Supporting patients in making informed decisions about their healthcare is a cornerstone of ethical medical practice, facilitating patient autonomy and trust between patient and doctor (Cocanour, 2017; General Medical Council, 2008). This is particularly pertinent in surgery where consent is typically a formal documented process with medico-legal importance that helps protect both patient and surgeon. Informed consent requires that a patient receives and retains the nature, risks and benefits of proposed treatments, together with any alternatives, in a form, language, and manner that enables them to understand it. They must be competent enough to make a decision about this aspect of care, and the decision must be made voluntarily without coercion (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988; Mallardi, 2005).

The necessary time should then be given for patients to make a considered choice. This process often takes the form of a verbal discussion, with provision of supplemental materials such as a written explanation in an information leaflet, and drawing pathology and treatment options, based on a patient’s needs, wishes and priorities. However, despite these efforts there remains a call to improve current practices to ensure effective execution of this process (Agozzino et al., 2019; Cawich et al., 2013; Joolaee et al., 2017; Ochieng et al., 2015).

Figure 1. Example of an evolving drawing to explain cholecystectomy and potential complications. Updates to the drawing are indicated in blue, with examples of the surgeons explanation below each panel. Cartoon sequence based on a drawn explanation of cholecystectomy by Miss Anna Paisley, Consultant General Surgeon.

Vision is the most developed human sense, making images an appealing communication aid which may transcend barriers of language, culture, and education (Pratt and Searles, 2017). From an evolutionary perspective, the ability to quickly interpret and remember one’s visual environment (e.g. recognising friend, foe, and food from a safe distance) is vital for survival, so it is unsurprising that memory for visual material is so well developed. Visual stimuli are more efficient than words for describing visuospatial relationships such as shape, position, orientation, and size. This makes images particularly valuable for explaining concepts of anatomy, pathology, and surgical intervention (Figures 1-3).

Figure 2. Example drawings sketched for patients to explain cholecystectomy (left) and a hernia repair (right). In clinical practice, these schematic representations are made in real-time, accompanied by verbal discussion, and adapted to patient questions and understanding. Drawings courtesy of Mr. Dimitrios Damaskos, Consultant General Surgeon.

Figure 3. Surgical illustration sequence explaining a decompressive craniotomy for subdural haematoma, by Dr. Ciléin Kearns.

The authors noted that surgeons frequently draw and show images to patients when consenting them for operations (Figure 2). This was observed by the authors in both acute presentations and routine clinic settings, across numerous surgical departments, and specialities. A literature review on the value of visual materials to patients undergoing surgery on the PubMed database revealed two relevant original articles. The first concluded that visual aids improved the understanding and retention of information given during the informed consent process of children with appendicitis (Rosenfeld et al., 2018). The second, considering the collective professional opinions of 100 surgeons on the value of drawing in their practice, found that drawing provides benefits for patients across numerous domains of surgical practice, including ‘improving the consent process’ (Kearns, 2019).

A further editorial (DeGeorge et al., 2017) on techniques to improve informed consent in hand surgery proposed that a standardized set of patient education materials including literature and illustrations be used. The authors also stated that using a sterile glove as a visual aid for simulation of soft tissue coverage of the hand was effective when explaining the procedure to patients. However, these proposals were based on the senior author's cumulative experience and do not account for the patient’s perceived value of these methods in giving informed consent.

Most of the other published research on the value of visual materials as a communication tool has almost exclusively been on its use in improving adherence to medications. A systemic review (Barros et al., 2014) demonstrated that pictograms could serve to enhance visual attention, recall and adherence of the instructions provided for the use of medications.

The purpose of this audit was to expand on this work and gather data about the patient perception of these drawings compared with other visual materials commonly used during the surgical consent process.

The primary outcome was to determine the value of visual materials to patients in this setting. The secondary outcomes were to determine whether the value of visual materials correlated with the complexity of the operation, and how drawing for patients was valued compared with other visual materials.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted on adult patients undergoing elective general surgical procedures at a tertiary public hospital over a six-month period. When patients were admitted to the Day Surgery Unit on the day of surgery, they were offered a questionnaire (Appendix A) by the receptionist. To determine whether informed consent had been obtained, the patients were asked to rate their understanding of their diagnosis and reason for surgery. The questionnaire also asked patients whether they received any visual materials, and their perceived value of visual materials in the process of giving informed consent. Visual materials were categorised as “drawings made by surgeons” and “other forms of images”. The latter represented any visual material that was not drawn by a surgeon, i.e patient scans, and illustrations in leaflets, websites or books etc. No identifying information was collected and patients remained anonymous. There was no direct involvement of the operating surgeons and they were blinded to the results throughout data collection.

The standard procedure at this hospital was to obtain informed consent prior to, as well as on, the day of surgery. The patients initially received an explanation of their pathology and proposed operation from a surgeon, either in a clinic or ward setting, and provided their consent prior to admission. Patients were then re-consented on the day of surgery. Questionnaires were provided on admission and collected after this second consent discussion had taken place, at which point the resources of both discussions could be considered.

Following data collection, three senior consultant general surgeons were given a list of the surgeries undergone by the patients, and independently rated the operations as: ‘simple’, ‘moderate, or ‘complex’. In the instance where the three ratings differed, the majority rating was determined to be the overall rating.

Results

The questionnaire was completed by 244 patients. The details of the visual materials used and the type and complexity of operations performed are described in Table 1.

80% of patients (n=195) strongly agreed (SA) that they had been able to give informed consent while the rest only agreed (A) as per Table 2. In patients who strongly agreed with being able to provide informed consent, twice as many had received visual materials compared to those who simply agreed (50% SA vs 27% A). This may represent an increased degree of understanding and satisfaction with the consent process following the provision of visual materials.

62% of patients (n= 152) received at least one form of visual material, of which the majority were surgeon drawings. 29% of patients (n=71) received both a drawing and another form of image.

Value of visual materials

All patients who were provided with a surgeon’s drawing found it helpful in understanding their surgical procedure. All but one participant provided with other forms of image found it helpful. Out of those who did not receive any visual materials (n=93), 33% of patients stated that they would have found either a drawing, other image or both helpful. This suggests a missed opportunity to improve the consent process for a third of these patients.

Value of visual materials and complexity of the operation

Thirty-four patients were excluded from this sub-analysis as they had atypical surgeries, left this response on the questionnaire blank, or the operation could not be determined from their response. Surgeons were more likely to draw or provide other forms of images when consenting for moderate and complex operations compared to simple operations. The value of visual materials to patients correlated with this, where both drawings and other images were significantly more useful and desired by patients consenting for moderate and complex operations than simple ones (Figures 4 and 5).

The potential value to patients of drawings and other images could be considered the combination of those who received and valued these resources (darker green and orange portions of the bars in Figures 4 and 5 respectively), plus the proportion of patients who did not receive them, but felt they would have helped them make an informed decision when consenting to surgery (light green and yellow portion of the bars in Figures 4 and 5 respectively). The latter could be considered potential ‘missed’ opportunities to improve the consent process. Combining this data indicates the proportion of patients who value drawings and other images to help them make an informed decision about surgery (Figure 6).

For both drawings and other images the differences observed in value of simple vs moderate, and simple vs complex operations, were significant (p<0.01, Chi-squared test). The differences between moderate and complex operations were not significant for either drawings or other images. It can therefore be concluded that visual resources were significantly more valued for moderate and complex operations than for simple ones. Although drawings appear to be more valued than other images, these differences were not significant in the patient sub-analysis (n=210), or overall patient group (n=244). Overall, patients valued receiving visual resources of any kind over not receiving them. (p<0.01 Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

This study indicates that patients benefit from visual resources being provided as part of the consent discussion, particularly for moderate and complex operations. This supports Rosenfeld’s findings that parents or guardians receiving a visual aid in addition to the standard consent form when consenting children to surgery demonstrated improved comprehension and retention.

Surgeons’ sketches tend to be relatively crude images made to explain pathology and proposed operative intervention (Figure 3), so it was intriguing to find they were valued as highly as other forms of images. Surgeons’ drawings are made quickly under the pressures of busy clinical environments, and tend to lack artistic merit such as accurate proportions, shading, and anatomy.

The authors propose an explanation for the value of visual resources used when exploring surgical care options with patients, based on cognitive research (summarised in Table 3). Making an informed decision about a surgical treatment requires that a patient receives the necessary information in a form, language, and manner that enables them to understand it. Most patients will be unfamiliar with human anatomy, physiology, pathology, and healthcare interventions, which must be explored with discussion.

Human working (active) memory has a limited capacity to hold information. The more ‘bits’ of information being retained at once, the greater the ‘cognitive load’, or mental strain (Halarewich, 2016). Furthermore, information that is presented to a person who is uninterested or not ready to process it is effectively noise (Lidwell et al., 2010). In order to maximise patient understanding and retention, effective communication should minimise the cognitive load required to comprehend new ideas (Sweller, 1994). Discussing medical information such as a diagnosis and proposing operative intervention could induce a large cognitive load on a patient, and negatively impact informed consent. One would expect this problem to increase with greater complexity of the proposed operation.

Images can communicate anatomical information and visuospatial relationships more concisely and clearer than words, reducing the amount of words or ‘bits’ required to explain them (Vekiri, 2002). ‘Bits’ of information can be ‘chunked’ to make retention of more information easier (e.g. memorising a phone number in groups of numbers rather than as single digits, or several words by using an acronym). Learning by chunking theorises that the brain processes information cognitively, instead of just memorising the characteristics of the stimuli it is presented with (Fountain and Doyle, 2012; Miller, 1956). The recoding of information into ‘chunks’ increases the capacity of working memory and facilitates recall. When drawing for a patient, the ‘bits’ of information in an image are gradually built up over time, allowing them to be processed in sequences that can be chunked (Figure 7). In a similar way, other images (e.g. medical illustrations) may be simplified to reduce unnecessary detail, and stylised to accentuate relevant detail, which both can make information easier to comprehend.

Increasing the dimensions in which information is presented (e.g. verbal [audio] explanation plus drawing [visual]) allows more bits per chunk. Verbal and visual information are stored in separate areas of the brain, so the mixed use of image and word creates multiple points of reference to aid comprehension and recall. This ‘Dual Coding Theory’ of cognition (Paivio and Csapo, 1973) describes the human mind as comprising of two functionally independent systems where visual and verbal information (codes) are processed differently along distinct channels (Dewan, 2015; Thomas, 2014). The theory also hypothesises that the visual and verbal codes are additive in their effect on recall, with the contribution of imagery being substantially higher than that of verbal code.

With drawings, the pace of explanation is rate-controlled by the speed at which a surgeon can draw and speak. This results in a gradual build-up of detail in both word and image, making complex information easier to process than its sudden presentation in a pre-constructed image or leaflet. Furthermore, the information represented in a drawing is filtered through the surgeon’s brain; and so can be dynamically tailored to a patient’s needs and understanding in real time, responding to questions and social cues (e.g. confusion, fear), unlike a pre-created visual (Figure 7). Given the suggested value in providing visual materials to patients undergoing surgery, and common practice of drawing for patients demonstrated in this and previous studies (Kearns, 2019), it is interesting that training in drawing skills does not feature in current surgical curricula.

Another advantage of surgeon’s drawing for their patients is that the patient experiences a clear investment of interest and effort from the surgeon on their behalf, which may build rapport, trust, and serve as a memorable experience. The physical ‘artefact’ of a drawing or other image can also be helpful to show family, and to reference later when deciding if they should proceed with an operation.

Limitations

This paper presents the value of drawings and images to elective general surgery patients in a single tertiary hospital. Further research is required to determine if these findings hold true across other specialities, and in the emergency surgical setting. In this study, all forms of image other than surgeons’ drawings were combined into one category. Further categorising these (e.g into radiology, leaflets) could help differentiate which type of image is most valued by patients for different operations and settings. This study only captured the opinions of patients who had agreed to undergo surgery, thereby excluding a proportion of patients who declined surgical intervention.

All patients felt that they had been able to give informed consent regardless of whether they were provided with any visual materials. This suggests that the current consent strategies are successful, and optimisation may only aim to improve the patient experience. It is worth noting that providing visual resources, while helping to explain the procedure, would not necessarily address the other components of the consent process (risks, benefits and alternatives to the procedure). As such, the context of visual resources being provided as part of interactive discussion with a surgeon is important.

Future research

The authors suggest that research into the following areas would help gain further insight into the use and value of visual materials in the consenting process:

· impact of use of visual materials upon the time taken to obtain informed consent

· perceived value of visual materials in patients who have declined surgery

· value of different sub- categories of visual materials i.e. radiology vs illustrations in leaflets

· design of a grading system to quantify ‘communication effectiveness’ for further study and to aid design of training resources

Conclusion

This paper is the first to substantiate evidence that surgical patients value their surgeons drawing for them, and provision of other visual resources, as part of the informed consent process. Visual materials were more valued by patients when surgeons used them to explain moderate and complex operations. This study identified that there was a missed opportunity to improve the informed consent process for a third of patients who did not receive visual resources before consenting to surgical intervention. Further research could inform optimisation of drawing and other visual resources, and the design of practical training materials to improve surgeons’ ability to communicate with drawings.

References

Agozzino E, Borrelli S, Cancellieri M, et al. (2019) Does written informed consent adequately inform surgical patients? A cross sectional study. BMC medical ethics 20(1): 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0340-z

Appelbaum PS and Grisso T (1988) Assessing Patients’ Capacities to Consent to Treatment. New England Journal of Medicine 319(25): 1635–1638. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198812223192504

Barros IMC, Alcântara TS, Mesquita AR, et al. (2014) The use of pictograms in the health care: A literature review. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 10(5): 704–719. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.11.002

Cawich SO, Barnett AT, Crandon IW, et al. (2013) From the patient’s perspective: is there a need to improve the quality of informed consent for surgery in training hospitals? The Permanente journal 17(4): 22–6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-032

Cocanour CS (2017) Informed consent-It’s more than a signature on a piece of paper. American journal of surgery 214(6): 993–997. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.09.015

DeGeorge BR, Archual AJ, Gehle BD, et al. (2017) Enhanced Informed Consent in Hand Surgery. Annals of Plastic Surgery 79(6): 521–524. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000001256

Dewan P (2015) Words Versus Pictures: Leveraging the Research on Visual Communication. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research 10(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v10i1.3137

Fountain SB and Doyle KE (2012) Learning by Chunking. In: Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 1814–1817. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_1042

General Medical Council (2008) Consent: patitents and doctors making decisions together. Available at: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/consent---english-0617_pdf-48903482.pdf

Halarewich D (2016) Reducing Cognitive Overload For A Better User Experience. Available at: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2016/09/reducing-cognitive-overload-for-a-better-user-experience/

Joolaee S, Faghanipour S and Hajibabaee F (2017) The quality of obtaining surgical informed consent. Nursing ethics 24(2): 167–176. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0969733015584398

Kearns C (2019) Is drawing a valuable skill in surgical practice? 100 surgeons weigh in. Journal of visual communication in medicine 42(1): 4–14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17453054.2018.1558996

Lidwell W, Holden K and Butler J (2010) Universal Principles of Design: 125 Ways to Enhance Usability, Influence Perception, Increase Appeal, Make Better Design Decisions, and Teach through Design. Rockport.

Mallardi V (2005) [The origin of informed consent]. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale 25(5): 312–27. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16602332

Miller GA (1956) The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review 63(2): 81–97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043158

Ochieng J, Buwembo W, Munabi I, et al. (2015) Informed consent in clinical practice: patients’ experiences and perspectives following surgery. BMC research notes 8: 765. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1754-z

Paivio A and Csapo K (1973) Picture superiority in free recall: Imagery or dual coding? Cognitive Psychology 5(2): 176–206. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(73)90032-7

Pratt M and Searles GE (2017) Using Visual Aids to Enhance Physician-Patient Discussions and Increase Health Literacy. Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 21(6): 497–501. DOI: 10.1177/1203475417715208. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28614954

Rosenfeld EH, Lopez ME, Yu YR, et al. (2018) Use of standardized visual aids improves informed consent for appendectomy in children: A randomized control trial. The American Journal of Surgery 216(4): 730–735. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.032

Sweller J (1994) Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction 4(4): 295–312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-4752(94)90003-5

Thomas N (2014) Dual Coding and Common Coding Theories of Memory. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/mental-imagery/theories-memory.html.

Vekiri I (2002) What is the value of graphical displays in learning? Educational Psychology Review. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016064429161