The role of comics in public health communication during the COVID-19 pandemic

This is the ‘Accepted Manuscript’ version of: “The role of comics in public health communication during the COVID-19 pandemic” published by Taylor & Francis in The Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine on 9/7/20, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/17453054.2020.1761248

Authors: Ciléin Kearns, Nethmi Kearns

Abstract

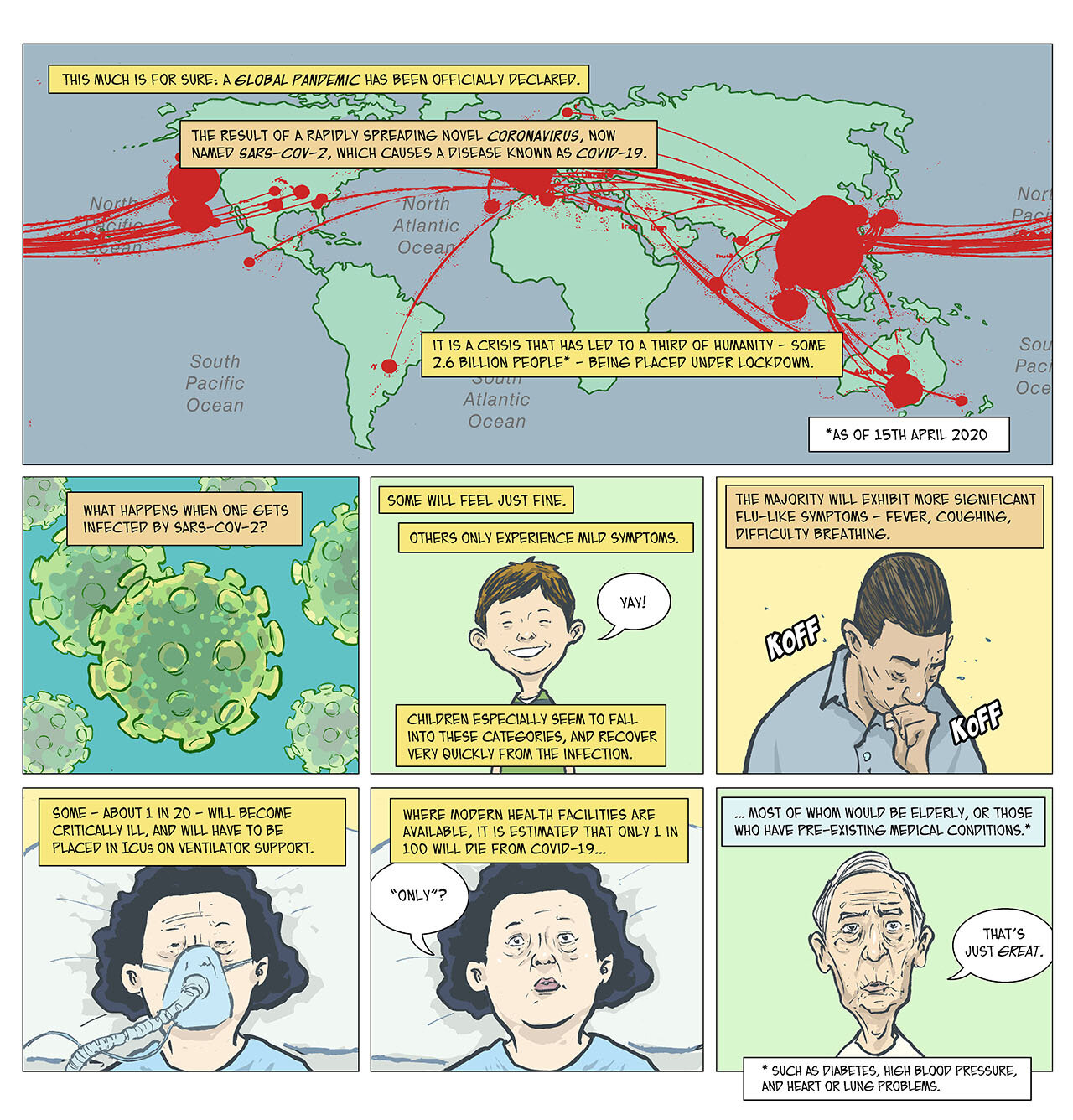

As the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps the globe, evolving containment measures have created an unprecedented need for rapid and effective science communication that is able to engage the public in behavioural change on a mass scale. Public health bodies, governments, and media outlets have turned to comics in this time of need and found a natural and capable medium for responding to the challenge. Comics have been used as a vehicle to present science in graphic narratives, harnessing the power of visuals, text, and storytelling in an engaging format. This perspective paper explores the emerging role and research supporting comics as a public health tool during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Comics, graphic medicine, public health, public engagement, health communications

Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps the globe, rapid evolution in national and global containment measures has followed. This has created unprecedented need for rapid and effective science communication that is able to engage the global public in mass-scale behavioural change. Comics are proving themselves a natural and capable medium for responding to this challenge, harnessing benefits from both image and text media, woven together in related sequential art to offer the additional opportunities of narrative communication. Unfamiliar and complex ideas may be built up in a paced way over panels. The use of simplification, schematic representation, and metaphor can help make abstract concepts tangible. As a familiar entertainment medium, comics are accessible and enjoyed by a wide range of audience demographics, and readily able to be shared on social media for efficient mass dissemination of information.

Public engagement with science is crucial at this time

When scientists do not participate in science communication, the public narratives are shaped without an informed expert voice, instead determined by interpretation, extrapolation, opinion, and misinformation. This can cause real harm in a public health context, exemplified by the anti-vax movement which has resulted in lowered herd immunity, leading to largely preventable outbreaks of measles in numerous countries like Samoa, Italy and USA.(1-3).

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation and non-compliance with containment measures threatens life on a larger scale, where the public has no inherent immunity to the disease, there is currently no treatment or vaccine, and the threat of healthcare saturation is an undeniable reality for some of the hardest-hit countries. This is a time which calls for the distribution of informed, accessible information that has the capacity to persuade significant behavioural changes such as strict self-isolation and social distancing. The mass cooperation of the publics is vital in a pandemic, so beyond simply educating, efforts must also support adherence to potentially very strict and sudden measures such as a nationwide lockdown. In democratic societies where governing bodies are unwilling or incapable of imposing tough quarantine measures like those successfully implemented in China in response to COVID-19, the role of communication which not just informs, but compels positive action is all the more critical (4).

Why use comics?

Comics are an interesting medium for communicating medicine where a concept can be built-up over a series of panels which weave together images and text in graphic narratives. The reader plays an active role in this exchange as they must engage their imagination to figure out the story of what has happened between panels. They also control the pace at which information is introduced by the time they spend reading and looking at each panel. Together these make the experience of reading comics slightly unique for each person. In terms of education, comics leverage ‘dual coding’ theory whereby comprehension and retention of information is improved by inclusion of both visual and text dimensions of information.(5) The medium itself is widely used and enjoyed, making it attractive vehicle for sharing public health information in an engaging way.

Since the initial naming of the virus now known as COVID-19, racist rhetoric has exacerbated the global harm of this pandemic resulting in (on the basis of perceived ethnicity) families being evicted from their homes, children bullied at school, students suspended from their studies, businesses declining to serve customers, a foreign employee being dressed as a Hand Sanitiser dispenser, Newspaper headlines telling Chinese children to stay home, a University Health Service normalising xenophobia as a reaction to COVID-19, public harassment and violence against individuals.(6-10) This highlights the importance of both tackling and not further exacerbating racism in public health strategies.

Figure 1. Simplification of characters shifts visual representation from the realistic to the symbolic. The more symbolic they are, the more people they could be considered to represent. This makes it easier for those reading comics to project their identity into the narrative and relate to characters and situations. From: “Why should we stay 2m away from others when socially distancing?” by Dr Ciléin Kearns (Artibiotics).

The simplification of characters in comics shift visual representation of people from the realistic towards the symbolic, with a ‘stick figure’ being an extreme example. This makes it easier for viewers of any demographic to project their identity into the narrative and empathise with characters, giving more relevance to the situations observed (Figure 1).(11) A variation on this idea of abstraction is the use of non-human characters, such as Sonny Liew’s cute anthropomorphised animals in his “Baffled Bunny” series (Figure 2). At a time when racism is inflaming a global crisis, it is critical to both help audiences empathise with the experiences of targeted individuals, and to disrupt associations between ethnicity and COVID-19.

Figure 2. Excerpt from “Baffled Bunny in OK with that” by Sonny Liew, in consultation with Dr Hsu Li Yang. Professor Alex Cook, and Dr Hannah Clapham. In this series, cute anthropomorphised animals explore questions about COVID-19. These characters are not tied to particular human demographics such as ethnicity or gender, which may make it easier for audiences to ‘see themselves’ in and relate to the narrative.

Narratives can facilitate ‘emotional contagion’ where the reader ‘catches’ the emotional state of the character(s) or situation.(12) Stories can be crafted to encourage a particular response, e.g., concern when a character’s actions put lives in danger, or joy in response to a healthy recovery. Key for public health interventions, behaviours can be modelled and their long-term outcomes connected in an emotionally engaging but safe environment, allowing readers to learn from both positive and negative examples. While such techniques may be helpful when used to encourage healthy behaviour, emotionally charging healthcare information may not always be appropriate, such as when providing balanced information to support patient decision-making on treatments like surgery or chemotherapy - context is key.

Comic art is unconstrained by the rules of reality governing visual media such as photography. This allows abstract concepts to be made tangible such as showing coughs spread clouds of infective material which is invisible in life, and representing the presence of infection (which may be asymptomatic or subtle) through the use of clear distinctive colour (Figure 3). Metaphor is another powerful tool to represent ideas in a corporeal and memorable way, such as ‘bursting your isolation bubble’ (Figure 3, panel 3) or ‘a tsunami of COVID-19 cases overwhelming healthcare’, (Figure 3, panel 5).

Figure 3. Comics can bend the rules of reality to more clearly communicate ideas. In panel 1, a ‘cough cloud’ is drawn visibly to show the spread of COVID-19. States of health (cyan) or infection (red) are made clear by colour throughout the comic. Visual metaphor makes the concepts of ‘isolation bubbles’ and a ‘tsunami of new cases’ tangible. From:“Why does the number of cases keep rising after lockdown?” by Dr Ciléin Kearns (Artibiotics).

Comics have been successfully used in healthcare settings to facilitate patient education, adherence, and decision-making in both mental and physical conditions.(13) A study analysing the impact of an educational comic about AIDS on knowledge and attitudes found that significantly higher mean levels of knowledge were recorded at post-comic testing in the experimental group compared to those who did not receive the resource.(14) A randomised controlled trial in an Emergency Department comparing the effect of standard discharge instructions on wound care to instructions including cartoons, found that patients who received instructions with cartoons were more likely to read the resource, answer all wound care questions correctly and be more compliant with wound care.(15) Similar successes have been achieved when using comics to deliver information on skin cancer, depression, and diabetes.(16,13,17) Furthermore, comics have also been shown to transcend language and socioeconomic barriers. A three-arm intervention study undertaken in children with amblyopia whose parents had poor local language skills and were living in a low socio-economic area demonstrated that a cartoon storybook intervention was the most effective resulting in 89% adherence of occlusion therapy when compared to 55% in the control group.(18)

Comics have been used successfully in science communication during the current Covid-19 pandemic. Many terms such as ‘social distancing’ and ‘flattening the curve’ went from textbook jargon to household conversation in a matter of days to weeks around the world. Many key health bodies, governments, media outlets, and creators, have found comics a natural medium for sharing such terminology and related science with the public. Notable examples include the ‘COVID-19 Chronicles’ from the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (Figure 4), Toby Morris’ comics explaining public health science for The Spinoff news outlet (Figure 5) Sonny Liew’s Baffled Bunny series and ‘The Moment’ comic (Figures 2, 6 and 7) Weiman Kow’s ‘Comics for Good’ initiative (Figure 8), Whit Taylor and Allyson Shwed’s ‘COVID-19 Myths, Debunked’ (Figure 9), Sesame Street’s ‘how to explain’ COVID-19 to your children, and Fishball’s ‘Disinfect’ webcomic for ‘My Giant Nerd Boyfriend’ (Figure 10).(19-27)

Figure 4. A comic from the ‘COVID-19 Chronicles’ series from the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine. The series is framed as an “Ask an Expert” featuring Dr Dale Fisher, Chair of the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), a Professor at NUS Medicine, and Senior Consultant at the National University Hospital’s Division of Infectious Diseases. Illustrated by Andrew Tan.

Figure 5. Illustrations from an animated comic created by Toby Morris for a collaborative article with Dr Siouxsie Wiles exploring the science of COVID-19 for The Spinoff. This comic presents contact-free greetings as alternate behaviours which can help reduce the spread of COVID-19.

Figure 6. Excerpt from “The Moment” written and illustrated by Sonny Liew, in consultation with Dr Hsu Li Yang. Sonny reflects on the COVID-19 pandemic and what the future may hold in a form that makes topics like geopolitics and public health science accessible. Questions such as the balance of economic depression versus the loss of life are explored with scientific narration humanised by tongue-in-cheek responses from the characters.

Figure 7. Excerpt from “The Moment” written and illustrated by Sonny Liew, in consultation with Dr Hsu Li Yang. Here Sonny humanises a scientific commentary with a sea of diverse faces, more of which ‘die’ as the panels progress. This is represented symbolically with contrasting red skulls replacing people in an increasingly claustrophobic composition. Sonny then leads our emotions from this dark and serious place to a light-hearted conclusion in the next three panels. This is a beautiful example of the emotional dimension a graphic narrative can add when communicating science.

Figure 8. Excerpt from “Separating Facts from Fiction” by Weiman Kow for her ‘Comics for Good’ initiative. This comic explores the harmful effects of misinformation and panic in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 9. Excerpt from “COVID-19 Myths, Debunked” by Whit Taylor and Allyson Shwed. This comic tackles harmful myths about COVID-19 in a clear and accessible form.

Figure 10. An excerpt from My Giant Nerd Boyfriend Episode 418: Disinfect, illustrated by Fishball. This webcomic has had tremendous engagement, accumulating 50,710 likes and 1155 comments within 2 weeks of publication. With a following of over 1.8 million people on Webtoon, the creator (Fishball) has tremendous reach with her art. Public health professionals can learn much from popular webcomics artists about disseminating information effectively in an enjoyable format.

The power of narrative can be wielded for health

The “knowledge deficit model” is a traditional top-down approach to science communication whereby information is provided to fill gaps in knowledge, under the assumption that this will result in people acting rationally once they understand it.(28) If this were true then simply educating people about the health dangers of alcoholism, smoking, and unhealthy diets, would result in cessation of these behaviours. This model is inherently flawed as humans are irrational with many heuristics (mental shortcuts) which affect how we perceive information and make decisions.

Psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on heuristics, which are used by people to make judgements quickly and efficiently as true rational decisions would involve weighing up factors that take up time and effort.(29) Whilst this leads to quick judgement, cognitive biases are introduced as the decision is based on past experiences, emotions and comparisons to known prototypes rather than being based on the merits of the facts presented to individuals.

From a public health perspective, this means that simply providing statistically and scientifically accurate information and imposing interventions are unlikely to result in adherent behaviours. The public needs to be presented information in such a way that their heuristic decision making, in fact, leads to the decision and change in behaviours desired by public health campaigns.

One way of supporting heuristic decision making is through narration and storytelling. Narrative thinking makes possible the interpretation of events by putting together a causal pattern which makes possible the blending of what is known about a situation (facts) with relevant conjectures (imagination).(30) Stories stimulate imagination, passion and create a sense of community that has a place in every culture and society. They help simplify complex ideas through narrative and convert complicated abstract ideas into more digestible and memorable chunks. Research has illustrated the utility of using narratives to communicate about health and that using visual messaging elements can be beneficial in communicating complex information.(31,32)

The power of narrative communication in public health may be best exemplified by a counter example; the anti-vaccine movement. This relies primarily upon unverifiable individual anecdotes which appeal to emotion and thrive upon fear. The medical community tend to respond with focus on impersonal statistically-significant and scientifically-sound trial evidence which is not exceptionally effective alone.(33) Combining the power of storytelling together with the science is a more effective method of countering such discourse. In an experiment where university students were randomised to receive either narrative descriptions or statistical information regarding adverse events for a fictitious disease, it was found that although both influenced their risk perception, the narratives had a disproportionately large effect. This was particularly pronounced when more emotional narratives were used, and the number of narratives presented could override their objective weight against statistical information.(34) This further demonstrates the role of narratives when communicating science information to support evidence-based informed decision-making or incentivise action in public policy.

Limitations

While this paper primarily explores the positive potential of comics as a public health tool, it would be remiss to imply inherent benefit with their use. Comics are simply a medium which offers some unique possibilities for engaging communication. Those wielding comics determine the messages shared. Their knowledge and ability will enhance or limit the accuracy, clarity, and effectiveness of comics created. Collaboration between science experts and artists skilled in science communication is key to successfully harness this medium in public health strategy.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented demand for rapid and effective scientific communication capable of engaging the public in behavioural change on a mass scale. Comics can be used as a vehicle to present science in graphic narratives, harnessing the power of visuals, text, and storytelling in a memorable and engaging format. This medium is familiar and accessible to wide audiences, can transcend language barriers, knowledge, age, and culture. Unfamiliar and complex ideas may be built up in a paced way over panels. Simplification, schematic representation, and metaphor can be make abstract concepts tangible. Stories which appeal to emotion are more powerful than purely data-driven arguments, and in an era of COVID-19 induced global pandemonium and misinformation, delivering the right facts to the right people could not be more important.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

1. Unicef. Vaccination vital to protect Pacific communities against measles [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/pacificislands/press-releases/vaccination-vital-protect-pacific-communities-against-measles

2. Siani A. Measles outbreaks in Italy: A paradigm of the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases in developed countries. Prev Med. 2019 Apr;121:99–104.

3. Benecke O, DeYoung SE. Anti-Vaccine Decision-Making and Measles Resurgence in the United States. Glob Pediatr Health. 2019;6:2333794X19862949.

4. Brueck H, Medaris Miller A, Feder S. China took at least 12 strict measures to control the coronavirus. They could work for the US, but would likely be impossible to implement. [Internet]. Business Insider Australia. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 26]. Available from: https://www.businessinsider.com.au/chinas-coronavirus-quarantines-other-countries-arent-ready-2020-3?r=US&IR=T

5. Aleixo PA, Sumner K. Memory for biopsychology material presented in comic book format. J Graph Nov Comics. 2017 Jan 2;8(1):79–88.

6. Gyamfi Asiedu K. After enduring months of lockdown, Africans in China are being targeted and evicted from apartments. Quartz Africa [Internet]. 2020 Apr 12 [cited 2020 Apr 18]; Available from: https://qz.com/africa/1836510/africans-in-china-being-evicted-from-homes-after-lockdown-ends/

7. Pitrelli S, Noack R. A top European music school suspended students from East Asia over coronavirus concerns, amid rising discrimination. The Washington Post [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2020 Apr 18]; Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/01/31/top-european-music-school-suspended-students-east-asia-over-coronavirus-concerns-amid-rising-discrimination/

8. Sakkal P. “Go back to your country”: Chinese international students bashed in CBD. The Sydney Morning Herald [Internet]. 2020 Apr 17 [cited 2020 Apr 18]; Available from: https://www.smh.com.au/national/victoria/go-back-to-your-country-chinese-international-students-bashed-in-cbd-20200417-p54kyh.html

9. Al Sherbini R. Coronavirus: Saudi Aramco says it’s dismayed with ‘human sanitiser.’ Gulf News [Internet]. 2020 Mar 11; Available from: https://gulfnews.com/world/gulf/saudi/coronavirus-saudi-aramco-says-its-dismayed-with-human-sanitiser-1.70307723

10. Kacala A, T Coffey L. Coronavirus bullying is a thing. Here’s how parents can deal. Today [Internet]. 2020 Mar 18 [cited 2020 Apr 18]; Available from: https://www.today.com/parents/coronavirus-bullying-thing-here-s-how-parents-can-deal-t175997

11. McCloud S. Understanding comics. Reprint. New York: William Morrow, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers; 2017. 215 p.

12. Simpson W. Feelings in the Gutter: Opportunities for Emotional Engagement in Comics. ImageTexT [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Apr 16];10(1). Available from: http://imagetext.english.ufl.edu/archives/v10_1/simpson/#eleven

13. McNicol S. The potential of educational comics as a health information medium. Health Inf Libr J. 2017 Mar;34(1):20–31.

14. A.Gillies P, Stork A, Bretman M. Streetwize UK: a controlled trial of an AIDS education comic. Health Educ Res. 1990;5(1):27–33.

15. Delp C, Jones J. Communicating Information to Patients: The Use of Cartoon Illustrations to Improve Comprehension of Instructions. Acad Emerg Med. 1996 Mar;3(3):264–70.

16. Putnam GL, Yanagisako KL. Skin cancer comic book: evaluation of a public educational vehicle. Cancer Detect Prev. 1982;5(3):349–56.

17. Pieper C, Homobono A. Comic as an education method for diabetic patients and general population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000 Sep;50:31.

18. Tjiam AM, Holtslag G, Van Minderhout HM, Simonsz-Tóth B, Vermeulen-Jong MHL, Borsboom GJJM, et al. Randomised comparison of three tools for improving compliance with occlusion therapy: an educational cartoon story, a reward calendar, and an information leaflet for parents. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013 Jan;251(1):321–9.

19. Yoong Loo Lin School of Medicine. The COVID-19 Chronicles [Internet]. The Covid-19 Chronicles. [cited 2020 Mar 25]. Available from: https://nusmedicine.nus.edu.sg/medias/news-info/2233-the-covid-19-chronicles

20. Morris T. The Side Eye #26: Viruses vs everyone. Three simple points about the science of Covid-19. The Spinoff [Internet]. 2020 Mar 25 [cited 2020 Mar 25]; Available from: https://thespinoff.co.nz/covid-19/25-03-2020/the-side-eye-viruses-vs-everyone/

21. Wiles S. The three phases of Covid-19 - and how we can make it manageable. The Spinoff [Internet]. 2020 Mar 9 [cited 2020 Mar 25]; Available from: https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/09-03-2020/the-three-phases-of-covid-19-and-how-we-can-make-it-manageable/

22. Liew S. Baffled Bunny in “OK With That” [Internet]. New Naratif; 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available from: https://newnaratif.com/comic/baffled-bunny-in-ok-with-that/share/xuna/2c9ec71f040ae43b350159093c4401bd

23. Liew S. The Moment [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available from: https://mothership.sg/2020/04/sonny-liew-covid-19-comic/

24. SesameStreet.org. Caring for Each Other [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.sesamestreet.org/caring

25. Kow W. Separating COVID-19 Facts from Fiction: Part 1 of 3 [Internet]. Comics for Good; 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available from: https://www.comicsforgood.com/weimankow/covid-19-misinformation-1-of-3

26. Taylor W, Shwed A. COVID-19 Myths, Debunked. The NIB [Internet]. 2020 Mar 22 [cited 2020 Apr 18]; Available from: https://thenib.com/covid-19-myths-debunked/

27. Fishball. Episode 418: Disinfect [Internet]. My Giant Nerd Boyfriend. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 26]. Available from: https://www.webtoons.com/en/slice-of-life/my-giant-nerd-boyfriend/418-disinfect/viewer?title_no=958&episode_no=418#

28. Simis MJ, Madden H, Cacciatore MA, Yeo SK. The lure of rationality: Why does the deficit model persist in science communication? Public Underst Sci Bristol Engl. 2016;25(4):400–14.

29. Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. London: Penguin Books; 2012. 499 p.

30. Robinson JA, Hawpe L. Narrative thinking as a heuristic process. In: Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct. Westport, CT, US: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group; 1986. p. 111–25.

31. Green MC. Narratives and Cancer Communication. J Commun. 2006 Aug 1;56(suppl_1):S163–83.

32. Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, Loscalzo MJ. The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 May;61(2):173–90.

33. Shelby A, Ernst K. Story and science: How providers and parents can utilize storytelling to combat anti-vaccine misinformation. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013 Aug 8;9(8):1795–801.

34. Betsch C, Ulshöfer C, Renkewitz F, Betsch T. The influence of narrative v. statistical information on perceiving vaccination risks. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2011 Oct;31(5):742–53.